After I finished training at Duke and served my two years in the Navy, I was recruited by several universities to join their staff. Indiana came up with the best offer. Become an assistant professor of medicine at full salary, but study for a year any place I wanted.

A sabbatical to start a job? Unheard of! I accepted and chose to work with one of the most brilliant research scientists in one of the ugliest towns in the U.S.

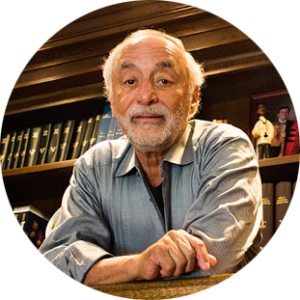

Gordon K. Moe PhD, MD directed the Masonic Medical Research Laboratory in Utica, New York.

MMRL was a small, two storied red brick building that occupied a tiny corner of several picturesque acres of the Masonic Home for Senior Living in the outskirts of Utica, a sad, broken little town halfway between Syracuse and Albany. Utica had one jewel: Grimaldi’s Italian Restaurant. Gordon and a few colleagues drank lunch there every day.

“Hiya’ Doc,” Joe the bartender called out as we walked in. Unbidden, he prepared Gordon’s extra dry Beefeater gin martini as we sat at the bar. A short, baldheaded, rotund Italian, Joe had been serving Gordon his two-martini lunch and a bowl of minestrone with crackers for years. “No olives in the martini,” Gordon once instructed Joe. “If I want a salad, I’ll order it. Takes up gin space. Same for ice.”

I accompanied Gordon and the others the first few days but my liver and wallet couldn’t handle the stress, and I bagged my own sandwiches after the first week. Besides, we had “happy hour” at five. No matter what I was doing, I had to stop and join the lab group in Gordon’s office to sip bourbon and talk shop until Gordon left for home at six.

What an incredible hour it was! Gordon led the discussion, never showing the slightest signs of his liquid lunch. Ideas flew around his office like flocks of birds flitting in and out of tree branches, swooping down to land briefly on Gordon’s desk, only to be shooed away by hard facts and replaced by new ideas, new hypotheses. It was the most intellectually exciting time of the day and provided fodder for next day’s or next year’s research agenda.

The problem was, at six, we “worker bees” had to return to our own labs to finish our experiments. This often took me till nine or ten at night.

Winter evenings were the worst. By that time, my ancient, rusting blue Ford—sitting for hours in the frigid upstate New York winter—had suffered cardiac arrest and required resuscitation. I had to open the car’s hood, unscrew the carburetor cover, suck some gas into it, and coax the Ford back to life. I performed this automobile CPR holding a shaking flashlight in my chattering teeth. The motor, annoyed at being disturbed, coughed, sputtered, and after several tries, finally displayed a return of spontaneous circulation.

My winter tires had studs, and, despite a total snowfall approaching 15 feet that winter, I usually made it home in twenty or thirty minutes. Only after the lab’s four-hour Christmas party did I have a problem. A telephone pole rose out of nowhere to hit the front of my car after I left the parking lot. Six feet of snow packed the base of the pole so it was like bouncing off a hard marshmallow. I just backed up and maneuvered around it.

Ten minutes later, a snow bank jumped up to snatch my front wheels. This was a bit more serious because here the marshmallow was soft and I got stuck in three feet of snow. An hour passed before a snowplow came along and dug me out. Fortunately, I had plenty of circulating antifreeze to protect me from the cold.

Joan had checked with the police and local hospitals by the time I arrived home two hours later, shivering from the snow but in one piece.