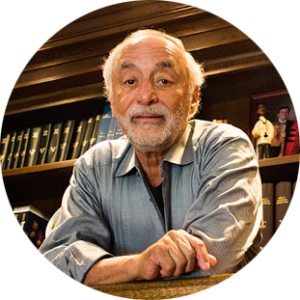

I was an intern at Duke University Medical Center in 1964, and was assigned a month with Walter Kempner. Dr. Kempner emigrated from Nazi Germany in 1934 and came to Duke Hospital as a medical scientist. Slim, medium height with dark hair, he was a handsome, charismatic autocrat who amassed a group of patients whose total numbers exceeded all other medical doctors at Duke combined.

His attraction? The rice diet.

At a time when no effective therapy existed for diabetes, high blood pressure, and kidney disease, Kempner found that eating white rice and fruit—and very little or no salt—cured or significantly reversed these diseases. Patients lost weight, blood pressure dropped, general health improved and patients flocked to Durham in droves. Duke had to establish “rice houses” in town at cooperating motels/hotels to serve rice, fruit and vitamin supplements because the hospital overflowed.

We made rounds in the morning to check on each patient. Kempner walked stiffly erect, hands clasped behind the back of his starched, long white coat, and stethoscope dangling from his neck. He stood for a moment at each patient’s bedside and allowed them one question, and one question only. Invariably, they asked about their urine. Kempner had the hospital collect every drop and analyze it for salt to see who was cheating. An occasional patient who snuck a pizza slice the day before offered hard cash for the urine of someone who followed the rules.

One day a wealthy New Yorker, head of a major corporation, was admitted to Kempner’s service for uncontrolled high blood pressure and weight loss. He was a big guy, probably more than three hundred pounds, with a huge gut hanging over his belt. Used to giving orders, he struggled with Kempner’s domineering ways. After three weeks in the hospital eating rice every day except Friday when he was allowed boiled chicken, the patient began to go stir crazy. On Thursday, he’d become euphoric, anticipating Friday’s chicken dinner, and on Saturday, he plummeted to the depths of depression, facing six more days of unrelenting rice.

On the third Saturday, he broke—just lost it. Seeing a tray full of delicious food for the patient across the hall, he bolted from his bed and grabbed whatever he could—it turned out to be a hardboiled egg—wolfed it down and, hiding his face with a napkin, snuck back to his bed, hoping no one saw him.

Not to be. A nurse reported the event to Kempner. When we made rounds the next morning, the CEO pinched his brow, squinted his eyes, squirmed, fidgeted in his bed, and looked everywhere but at Kempner. Kempner seemed oblivious, aloof, glaring down at him.

Finally, the patient couldn’t stand it any longer and asked his one question. “Dr. Kempner, how…um, how…um, how was my urine?” he finally blurted.

Kempner stared him in the eye and without a moment’s hesitation, said, “Urine? Your urine had one hard boiled egg in it!” He then spun on his heels and stalked out, leaving the patient aghast, his mouth open.

The man checked out of the hospital that afternoon and returned to New York on the first flight out of Durham.